between sagebrush and bougainvillea | Los Angeles

/It was, in fact, the sound of a pool pump being restarted, but in my head it sounded like a mountain lion breaking the quiet of the Mojave hills. A throaty gurgle, set against the backdrop of the sunburnt, chaparral-dusted slopes; the dusky shadows moving through scrubby sagebrush and grass turned gold at the edges. I was, perhaps, not far enough out of the dreamy Tahiti afterglow, or I may have just entered the golden Californian haze that would tint my trip like honey poured thin over glass. It would linger like perfume on film star silk and leave me dreaming of G-Wagons winding through khaki canyons. Dripping bougainvillea spilled magenta while dusty eight lane highways stretched toward the hazy silhouettes of distant ridgelines, rising from the dry shimmer of heat.

California really is a state of mind and over the three days I was there, I knew I fell deeper under the spell. I ate Trader Joe’s ube covered pretzels in a sun washed parking lot, the coating melting stickily over my fingers. Giant Dodges, Lincolns, GMs I’d never seen before manoeuvred clumsily out of the bays, I put my feet up on the hot leather seats and watched the chemtrails fade in an azure desert sky. It was the bigness, perhaps, that was my first real indication I was truly somewhere else. The eight-lane 405 North, Sacramento-bound; the crawl past Hollywood Boulevard; the slow climb toward the Getty; the split where the 101 curved away, Pico Boulevard, in your used, little bullet car, if we choose. And we did choose. Away from the snarl of freeways and the choreography of endless lanes there was another rhythm. Woodland Hills in the late afternoon, washed by a heatwave, the roads narrowed, the air softened, the hush broken only by sprinklers ticking across lawns, the lazy sway of jacaranda, American flags half-wrapped around their poles, sleepy in the heat.

When people dream of suburban America, this is the dream. Sprawled houses backed by the sepia hills, each home with a different geometry of porches, balconies, and shuttered windows. Air heavy with jasmine, hummingbird-hover still, buds spilling like red wine over stucco walls. The constant hiss of sprinklers, lawns the colour of emeralds, out of place and defiant against the buckwheat and flax of the scrub around. Front lawn signs proudly proclaimed that a child was now a Calabash Cub! and in front of a wicker porch swing, the community celebrated a Calabasas High School graduate’s acceptance to Ohio State, we cheered that someone had become a Westlake High School Basketball All Star. Comfortable, thriving America, Teslas glinting under bowing eucalyptus, pools lustrous turquoise behind high fences, secret oases of cool. There were boats and jet skis parked on palm-lined curving driveways; RVs hugging the sidewalk, dogs sheltered indoors in AC, away from desert heat and coyote interests. Candy-coloured roses trailed over whitewashed walls like melted rubies; oozing prosperity in the dust-bleached scrub; hibiscus, wide as teacups, drenched in sherbet shades opened like tropical suns.

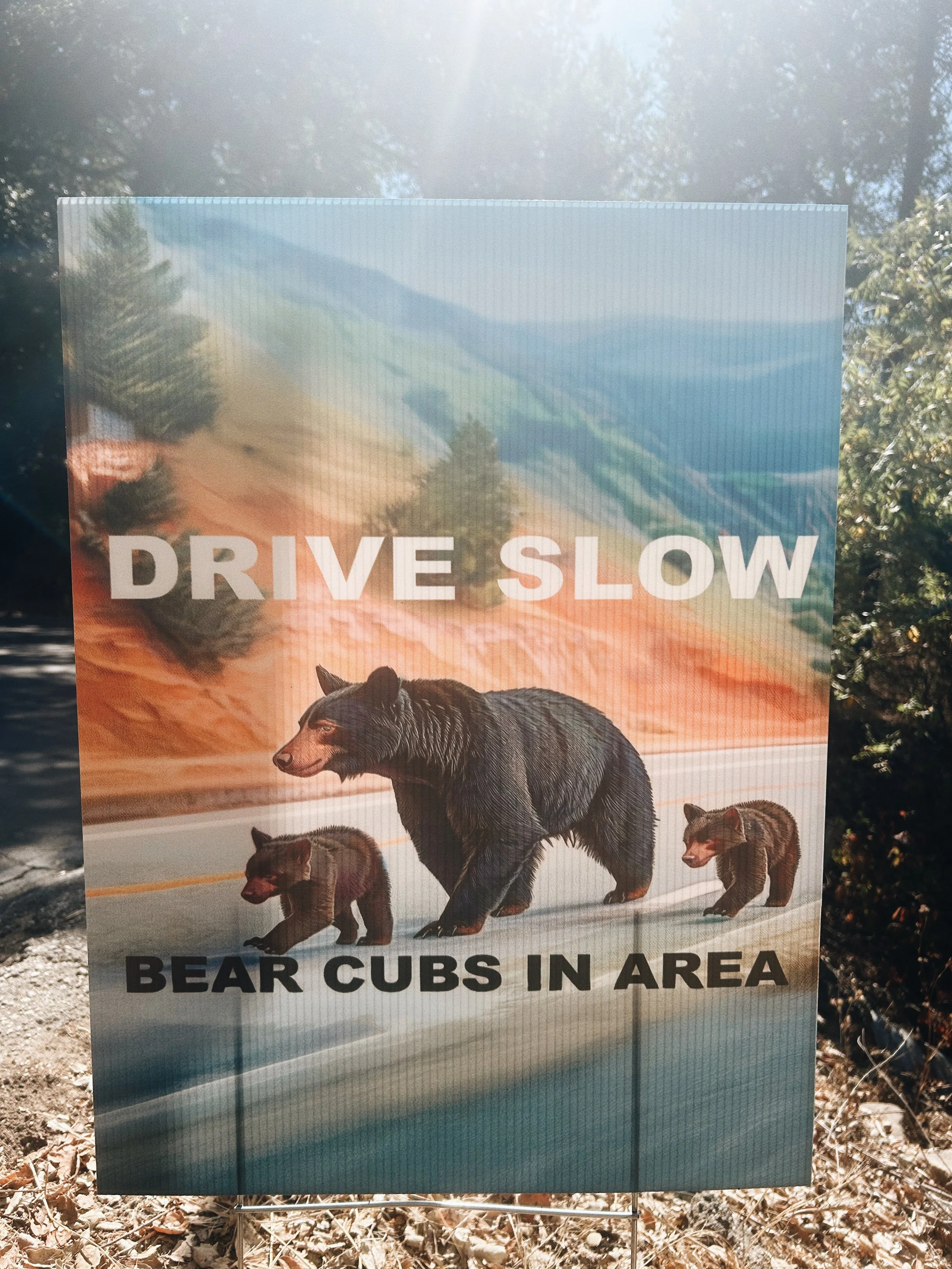

Woodland Hills, is, in that way, perhaps a product of its location. Halfway to the film studios and IT places and fortune whoevers of Hollywood; halfway to the free-spirited violet haze of the Santa Monica Mountains; Topanga Canyon steadily unspooling towards Malibu’s dreamy coastline. We followed that spool north, starting at the scrubby hillsides thick with chaparral and wild sage, leaves silvering in the sun, scrub oaks twisting like wicker, every bend smelling of eucalyptus oil and dust. There were hand-painted signs promising crystal healers and canyon cafés tucked under bowing sycamores, tie-dye flags caught between sagebrush and bougainvillea. It was my first brush with true California boho-glam and I was captivated. Signs warned us about families of bears with cubs; two dusky coyotes slipped back into the buckwheat; wild fennel feathered along the roadside, tangled with milkweed and morning glory.

Our little rental car climbed valiantly through the canyon, taking us over the scrub line, the road began to dip and fold, pressed tight by canyon walls the colour of sunburnt clay. Pines and sycamores gave way to bare rock, crumbling into the winding switchbacks, each turn revealing steeper cuts, ochre stone carved with a thousand dry seasons, the caress of a thousand suns. We stopped at lights for roadworks - the heat absolutely thick with silence; the cornflower sky miles high; the hawks wheeling lazily through the thermals and over the ridgelines, their shadows slipping across the asphalt curves. And then, without more warning than another merge-in turn, the light shifted - the horizon widening , the ocean shimmering, filling the windscreen with the pearl shells of a mermaid’s tail. The Pacific, laid out in front of us, hugging the Pacific Coast Highway on one side as it nuzzled the canyon on the other. The road exhaled towards Malibu, the salt-lick tang of Pacific air through the windows, surfboards lashed to roofs, lifeguard huts peeping out like jellybeans from paling sands.

We parked near Malibu Pier, white-clapboard wood extended over the foamy Pacific; the ocean water-colour green under the cotton clouds flowing over the Canyon; air heady with salt-mist, softening the edges of everything, like a gauzy filter. It was Saturday morning and Californians were arriving for brunch in colours to be the envy of Cape Cod; Mustangs raced south along to the PCH to Santa Monica; small dogs hopped out of convertibles. Malibu was the perfect shift after the canyon dreaminess: hazy, salty, playful. We walked to Surfrider Beach, where the Pacific was a sheet of silver glass, trembling where the light touched it.

In the veil of the popsicle-painted life guard huts denouncing the times for high and low tides, small children squealed at the waves, their footprints vanishing as fast as they were made. Retrievers lunged joyfully into the surf, shaking diamonds of water into the air and lines of surfers bobbed like seals just beyond the break. Surfrider was a bit of a surfer nursery - not quite the full body rollers of beaches like El Matador and Zuma, but enough of a curve that the braver enthusiasts could ride a watery prayer; waiting, rising, balancing, surrendering. Standing on the champagne yellow sand, I understood suddenly the appeal: to be completely given over to something wild, to borrow its rhythm for a few seconds. And that would be, in some ways, one of my lasting impressions of LA - that a sprawling, urban rush flourished within the confines of the fiercest of nature, balancing on a line between wildfire and wave, the tindered canyons behind and ahead, the restless sigh of the Pacific.

We crossed over the PCH (the traffic crossing told us to wait, emphatically, several times, which for some sun-touched, jetlagged reason we found deliriously funny) and so found ourselves switching Ripcurl for Brandy Melville at Malibu Country Mart, where the salt gave way to sage candles and pressed linen dresses. From surfboards to Céline bags in the span of a mile, how very LA. Whitewashed plazas blooming with jasmine, juice bars, straw hats, racks of gauzy kaftans in desert-hued silk waiting for suntanned shoulders. In one of those gauzy-white-and-denim stores, the kind that smell like salt and sage, a golden-haired shop assistant looked like he’d stepped straight out of a Beach Boys chorus.

Even the shop staff seemed styled by the ocean: tousled hair, skin tanned to honey caramel, denim worn soft as driftwood. I try to focus on the jackets, but instead I’m staring at California in human form, folding jeans. I’m stuck on his saltwater tan, sun-bleached blonde curls falling like sea-grass, back in the car, I’m planning my wedding. We go on to Santa Monica for souvenirs - the boardwalk sitting under a blanket of spun-sugar fog, the ferris wheel turning slowly in a haze of retro cloud, everything sepia-toned in the low light, somehow a little melancholic, tinged with salty nostalgia. The PCH steers us out of the fog and back towards the ochre of Topanga Canyon; our little rental couldn’t but we should have been playing the Beach Boys; or Lana; everything looks better from above my king; like aqua marine, ocean's blue , something about summer romance and rockpools. The Canyon heat washes through the car, cicadas humming somewhere unseen, dry grass bowing in the wind. I’m supposed to be programming the GPS to go to Sprouts, but in the afternoon sun, we’re bathed in gold and I’m configuring nothing; I’m thinking of my boho-beach-cowboy crush, the lived-in surf tinged denim, that hair with the warmth of sand; just like Topanga and Malibu, somewhere between the dust and the ocean, he’d woven himself into the haze of California itself.

If on Saturdays Californians go to Malibu, on Sunday they go into the city to hike Runyon Canyon, as we found out as we tried to find a parking at 8am in Hollywood (“somewhere around the 4700 block of Hollywood Boulevard”). We parked in a pleasantly leafy, spacious enclave near North Fuller Ave, following French Bulldogs and their Alo-clad; legging-ed owners to the East Trail. There was a fragile layer of cloud over the Canyon, a marshmallow dusting, the city hidden, until the dry blaze of the LA sun rose higher and turned the trails to gold. We had signed up to walk rescue dogs with a group - dainty Mojo; quiet and friendly; and the exuberant Brownie; flax hued like California itself. It was a winding trail, initially heavy on the silvery brush, but quickly the dusty switchbacks unwound before us, every turn promising a wider slice of sky.

It was clearly not just us who sought that out - the Canyon buzzed with chatter; dogs of all kinds frolicked through the ravine; tongues lolling, paws skimming over sandstone, their owners hustling to keep up. Three women with bouncing ponytails and oversized Stanley cups debated sorority drama at USC as if it were national news; muscle-beach types loped up and down the canyon shirtless, calves bronzed and veined, why hit the gym when you can hit the trail; or something like that. Behind us, two girls from our rescue-dog group were deep in conversation about LA real estate: “Glendale’s on the 5, Pasadena’s cute but honestly too far out.” A young couple in matching Dodgers caps sipped green juice from glass bottles, talking about matcha, Tesla charging points, LA things. As we climbed, guided by the pups, it became clear why this route is so well loved. Cacti bristled between the switchbacks, agave flaring like green torches against the dust - then suddenly, from the highest point of the Canyon, the city unfurled in all directions, a quilt of palm-lined streets stitched together by freeways.

Studio City shimmered in the distance, low haze giving it the look of a mirage; pools flashed turquoise in the Hollywood Hills below, hidden behind high stucco walls and magenta bougainvillea spilling over mansion gates. Like a movie cut-in, the Hollywood sign floated into view, sharp white against the sepia hills. The unblemished blue desert sky; a blanket over Los Angeles, leaving the city aglow with the light of dusky honeysuckle; dreamy; cinematic and Hollywood-ready. Our dogs returned to Venice Beach and we walked back to our car in burgeoning July heat; the neighbourhood was hushed; a pitbull panted through the grass; tired and chonky; palms shifted gently in lazy breeze. There was something there, that hot morning in Hollywood (new upcoming movie name?) - the wide cross walks; sun-bleached high rises, all seemed so familiar. Even the lines of palms, set against that desert-blue sky seemed almost synthetic, maybe not so strange, space may be the final frontier, but it's made in a Hollywood basement, so perhaps desert palms and golden breeze are too. Everything around us seemed both real and remembered, like a scene we’d stepped into once before, filmed golden, long ago, replayed in the heat as if the skyline itself were lit from a projector somewhere behind the Hollywood hills.

We had a taste for the hike and the wild tangles of Topanga at our feet so Sunday became the day of the trail. Topanga Canyon spooled out like dropped film in the immensity of the afternoon heat - maybe 1pm is not the best time to go for a hike in the borders of the Mojave? But. We were at the trailhead in Topanga State Park under boundless Californian sun; the trail began in a knot of dry chaparral: sagebrush, brittle buckwheat, and wiry manzanita twisting and tangling like hair in the wind. Scrub oak leaves clinked faintly, papery as coins, silver sage released its resinous perfume, dust puffed up at every step, talc-fine and sun-warmed, clinging to our ankles in a blizzard of copper. We climbed above the scrub-line, ever closer to the sun, where the brush thinned into open rockscape: ochre boulders sun-bleached to bone, scattered like Malibu seashells. The path curled upward through baked sandstone, the air heavy and still, the heat pressing; unbounded; nothing but sage in juniper shadow. The canyon opened into the true Santa Monica mountains: wide amphitheatres of stone and scrub, ridges rippling outward, looking over the mesas, bleached to parchment and ringed with heather and bundles of shrubs the colour of ripening avocado.

All around us, an impenetrable silence that came only in the high heat, the kind that swallowed voices, broken by the hiss of cicadas and the wing-beat of something far above. We had taken the Eagle Rock trail and had climbed the ridge line steadily toward the craggy collection of rocks, shrouded in brick-dust, ember-brown, terracotta. We again watched the Canyon unfold below in gold and shadow, Hawks wheeled lazily on the thermals, wings stretched wide, cutting across the silence. Somewhere in the distance, the thin keening of baby hawks carried, so faint it seemed woven into the hot air itself. But it is difficult to find words to describe the immensity - the horizon dissolving into a dreamscape of ridges and canyons, a watercolor blur of ochre and sage under the fierce white sun; heat rising in waves, turning the air thick and gold, as if we were walking through warm honey. The silence held, captivated, as if the canyon was holding its breath, birds floating like thoughts unspoken. It was too hot, too high, too dazzling, yet impossible to not to be present; to imagine being anywhere else. For all the plumes of ochre dust and sunburn, it felt like we’d stumbled into California’s secret heart, in that heat-hushed stillness, it felt less like a hike than like being folded into the canyon’s ancient rhythm, carried for a moment on the wing-beats of the cicadas and the calls of the hawks; the sun burning white and everything awash in gold.

About five minutes northeast of Woodland Hills, in the dry foothills of the Santa Monica Mountains is Calabasas, you might have heard of it? Hushed, sun-drenched and exclusive, it was believable that if things had lined up in your favor and you could, you would choose to live here. Calabasas looked dipped in soft pastels -rose-quartz stucco, pale sand, terracotta roofs curved against the honeyed sky; it had the air of a blushy Mediterranean village nestled into the California dust. Watched over by sprawling mansions in the hills; pools sudden splashes of azure; flowers unexpected bursts of rosé, the town hummed with the quiet buzz of affluence: G-wagons purring past, convertibles flashing in the heat, people in tennis whites and yoga sets gliding by like bees to the bougainvillea. Even the heavy quiet had a polished sheen, the kind that comes with manicured palms, linen-coloured hibiscus as big as satellites and frangipani cascades. The air shimmered with perfume: jasmine, lavender, roses heat-soaked until the scent seemed sweet and almost edible. Sunlight caught the spray of a marble fountain, scattering it into a prism while turtles sunbathed, unbothered by their own level of celebrity.

A cluster of cafes and shops in macaron-coloured stucco flowed in and out of fountained-paths, littered with fallen hydrangeas in sugar almond cream. We stopped into a linen-bright cafe; airy, minimalist, with splashes of yellow like bottled sunshine, I ordered an oat mocha and it tasted like California summer. It was around lunchtime, still quiet enough to slip in and out of shops. We stopped into a Williams Sonoma - less shopping, more stepping into a glossy spread from Better Homes and Gardens, cool air scented with cedar candles and citrus soaps. Shelves were stacked with copper pans, linen aprons, and enamel dishes that seemed destined for kitchens in the Woodland Hills: cavernous, comfortable, air-conditioned, candlelit. Each row gleamed like a catalogue: glassware catching the light, dutch ovens in desert colours sage, clay, sandstone. At our lunch spot, every corner seemed curated: marzipan-marbled tables, rattan chairs, potted lemon trees, pale oak counters glowing softly in the noon light. It felt like we’d left the canyon’s wild heat and entered a mirage made human: curated, sun-soft, and impossibly polished. If I could have borrowed this life a little longer, I would have, but I was lucky to have belonged to it for just the golden morning.

On our last afternoon, we returned to Topanga, via the sun-burnished Canyon, and to the silvering sage and manzanita of the State Park. Dead Horse Trail sounded satisfyingly wild-western, and it was. Densely hemmed in with thickets of juniper and buckwheat, murmuring in the heat, chaparral tangling at shin-height, dry and scratchy as straw. Scrubby compared to Trippet Ranch’s trails, the air smelled of eucalyptus and pine; the trail too narrow and dense to see around corners, leaving us somewhat uneasy in dusky cypress and olive shadows. We remembered the signs about a local bear mother and cubs; and a cyclist wearing a bear bell - the Californian wilderness leaving behind its honeysuckle, tender side and throwing us out into smoky muddles of rabbitbrush and eucalyptus, fragrant and trembling in the fragility of a desert heatwave.

Uncertain, we left the State Park and wandered to some of the small Topanga roads where cabins lay tucked behind eucalyptus groves, chimneys peeking at us through brittle leaves and desert gardens of cacti and agave. Not cabins in the sense of pick ups and red-neckery, more the boho-rugged magic of stone-built homes softened with desert ivy, architectural porches draped with hammocks and windchimes, hidden, secretive. Homes that looked less built than grown, rising out of the canyon as imagined by the California wilderness itself, at one with the dusky scrub and silvery cacti. Everything was tinged with that boho-Topanga magic, part commune, part fairytale, intoxicating like the cosmic incense sold in the little Topanga shops. We stopped into a few of them, a dusty cluster along Canyon Boulevard, where in a tiny grocery market we found produce piled high, heirloom tomatoes and peaches, skins taught and glowing in the sunset and sorbet tones of California. Fresh berries, local and wild, priced at $12 a carton; sun-burnished jewels, stained deep red and purple, plump and trembling, as if about to spill sweetness. The produce spoke to the sweeter side of the California sun; the nature that abounded from it; the people who’d built communities on golden dreams. It felt like maybe Topanga was California’s secret heart, wilder than the city, softer than the canyon, a place dreamed up in sage smoke and sunlight.

That afternoon when we were on the sun-baked trail to Eagle Rock I said to my sister that I'm lucky to have travelled a lot and loved a lot of places, but few settled into me the way California did, the way sunlight soaks into skin, hard to shake, left in a kind of shimmer. Maybe the California dream was always true. Not of Hollywood itself, but of California as a landscape, as a daydream, as a way of light. It wasn’t about fame or studios, but the surreal layering of ocean and desert, glamour and wilderness, the way each bled into the other. California isn’t only a place you see, it’s one you step into and feel yourself dissolve, borrowed by sunshine, borrowed by tide, by desert. Even the minutiae- a fountain turtle in Calabasas, a pitbull panting in the Hollywood grass, berries glistening in Topanga - carried a strange permanence, like film stills. The ocean, the honey-thick heat, the golden haze of canyon afternoons, they stitched themselves together into something bigger than a trip, with more of an effect on me - the California dream - to be there, to stay - it seemed, was stronger when leaving than arriving. Like wildflowers blooming in canyon cracks, California rooted itself quietly but insistently, impossible to forget, staying with me the way jasmine lingers on warm night air: delicate, persistent, impossible not to notice. California was a bloom, growing between the tindery mountains and the thrum of the Pacific; one that continues to blossom even after you leave.

“The California sun and the movie stars

I watch the skies getting light as I write, as I

Think about those years

As I whisper in your ear

I'm always going to be right here

No one's going anywhere”

Lana del Rey, How to Disappear

Recs, because I know you want to go to California now :)

Malibu Country Mart (Malibu, just off the PCH) - cute shops for browsing (also Brandy Melville, Lululemon), cute food places, G Wagons, no cute guys (bummer), good people watching though.

Drive the PCH - it’s now fully reopened after the Palisades fires, lots of reminders of that, but lovely Pacific views.

Santa Monica Pier - you just have to go ok? Parking is a mess, maybe do that in the morning.

Runyon Canyon - views of the Hollywood sign, amazing views in general, great people (and dog) watching (also hot shirtless guys on hikes yasss). Kind of an LA classic. Also big shout out to Ryan and Holly who organise the hikes with rescue dogs - you can find them on Air BnB experiences, the pups are absolutely adorable. On Sunday morning we found parking near Franklin Ave (use the East gate for the Canyon) but get there early because it’s streeeeessfull.

Topanga State Park via Trippet Ranch - the Trippet Ranch (paid) parking lot is closed until Sept 2025 for fire repair but there’s parking on the road. Cannot rec this highly enough - loads of trails, not too busy but not so quiet it’s creepy, absolutely beautiful. I wish I could go back already :)

Dead Horse Trail at Topanga State Park - cheap and lots of parking, views were pretty BUT be aware it's quite covered / brushy. Small roads nearby are cute to walk on though.

Topanga Canyon Blvd - such a beautiful road to drive. We saw coyotes, plenty of signs about bear cubs, beautiful climbs/drops and boho forest-y vibes, can’t rec enough but you know I lovee Topanaga :)

Sprouts Supermarket on Ventura Blvd - lots of good options food-wise (my beloved Olipop haha), staff were sweet, lots of parking. Pricey though.

The Commons at Calabasas (in Calabasas town) - overall just love the atmosphere, there’s lots of parking around, cute shops (also Sephora, Lulu, etc). Lots of dogs, g wagons, amazing people watching, make sure your outfit eats in case there’s a cute rich guy you can marry so you can stay forever :) Specific recs at the Commons:

Cross over the road to the other retail area for a super quiet and veeery well-stocked Ulta (Not Your Mother’s, Rizos Curls, LOADS of Pacifica, Tree Hut, etc.) sweet staff too

Back at the commons - La La Land Kind Coffee. This is up there with my favourite coffee shops in the world at this point, so adorable. Amazingly sweet staff, sooo aesthetic, seating outside, my oat mocha was amazing, cannot rec enough.

Superba - for lunch. Amazing vegan options - banana bread! Juice was super fresh, staff were really nice, we arrived at lunch without a reservation and got an amazing table outside. Super super aesthetic too.

Alamo Car Rental at LAX - yeah not a cute rec but they were really good! Didn’t charge extra for us being under 30, super friendly staff, clear signs etc. and efficient. Definitely would use again.

Canyon Gourmet, Topanga Canyon Blvd - super cute fancy, organic-y grocery store just off Topanga Canyon Blvd. There’s a cute little courtyard seating area, lots of fresh (but pricey omg) produce and drink options (Olipop for me, Layla had Stumptown Coffee and said it was worth the hype). Another fun wander.